I’m not very competitive. The last time I took part in a competition I was around eleven years old, when I had a little grey pony called Ritchie. You were supposed to walk around this big enclosure with about a dozen other people leading their horses along, then all stand in a line whilst the judges walk up to you in turn, poke and prod your horse, then you had to walk around the ring with your horse, as the judges watch you alone and everyone else just lurks in the middle. “Dude, this is boring as shit,” Ritchie says to me as we are standing waiting for the judges, biting my hand aggressively, painfully. “Why couldn’t we just go for a ride today instead?” He was right and I agreed, even as he was trying to kick me in the shins to voice his frustration. When the judges arrived, they groped Ritchie for a bit then said “Okay, you can go,” meaning that we could start our walk around the ring, but I misunderstood and left altogether. Surprisingly, I didn’t finish last, but I decided there and then that I wasn’t really in it for the winning, and that competitions would never again play a part in my life. I don’t particularly need any judges to tell me how much fun I’m having.

It is with some degree of alarm, then, that I suddenly realise I’ve entered an ultramarathon, and at the time I honestly can’t put my finger on why, especially as I can count how many miles I’ve run in my entire life up to that point on all of my digits. But over the months, I’ve pieced it together – I want to be fit enough to climb and ski some pretty long and steep couloirs this winter without collapsing from fatigue halfway through the day, and a quite effective way of doing that would be to just clock up as much leg-powered vertical height gain as possible, but I’m the kind of person who puts things off until the last minute, which isn’t really an effective training plan. If I had some kind of objective to work for that had a chance of some minor humiliation or simply wasting the 40 quid entry fee if I failed, I might be encouraged to put the effort in a little earlier. It seems to have paid off.

I spend the day before the race wandering around Chamonix with Georgie and Mary, both seasoned ultra runners with a few big races under their belts, and our trusty support team, Dan. I have a craving for protein, so we stuff our faces with raw fish at Satsuki before heading to registration to pick up our dossards, a free T-shirt, and oddly enough, an endurance-enhacing condom. Essential race wear. Looking around at the hundreds of pairs of running shoes pacing across the Triangle d’Amitié in the town centre, the start line and administrative office for the race, it all starts to feel a bit more real, and I find myself inwardly battling some minor attacks of terror. Once registered, the afternoon is spent messing about in Mary’s kayaks down on Lake Passy under a luxuriously-powerful late-summer sun. We go home, pack our bags and our stomachs, and try desperately to get some rest before the 0430 start. I drift in and out of sleep, having broken but convincing dreams about forgetting my running shoes.

Georgie’s picture of Dan, Mary, and me, messing about in boats

The alarm sounds thirty seconds after Aine has called to wish me good luck, but I’ve been awake and staring at the ceiling for ten minutes already. I fill a travel cup with super-strong coffee as I try to force down some sugary cereal with hot milk, this wonderfully childish breakfast being the only thing my stomach can cope with at the moment. I pull on my bright-green down jacket, looking like a lollypop with my black running tights, and go outside to wait on the curb for the taxi: Dan is driving Mary, Georgie, Carlton and I from Argentiere down to the start line.

There is a strange atmosphere in the Triangle d’Amitié as well over a thousand people arrive in dribs and drabs, the runners and their support crew. It feels like Monday morning at a music festival, when the drugs are starting to wear off and people are milling around almost unsure of what to do next; everyone is happy and enthusiastic, but on edge and amusingly jumpy. As we wait for half an hour, every now and then some sudden movement seems to jolt people into action, and as a whole we shuffle a few steps closer to the start line before deciding that it’s still a bit too early to be pressed up against each other. Finally, at a signal I didn’t notice and with about five minutes to go, we aim for our starting positions: chiseled statues of muscle and tendon force their way to the front as worried-looking men with pot bellies, already sweating, seem grateful to be pushed further back, towards the floodlit church. Lost, I follow Georgie into the crowd – we are somewhere between the back of the front, and the start of the middle. I am now genuinely scared of what is about to happen, and my witty and verbose commentary on the proceedings falters into nervous murmurs and feeble jokes.

There is a speech, there is cheering, we hold a minute’s silence. We are wished bon courage, there is a five second countdown, and I have a desperate urge to whimper “Wait, I’ve changed my mind…” as the pack pushes forward, carrying me along with them. A constant rustling noise fills the air, the sound of thirteen hundred rubber soles striking the ground. I take a series of deep breaths to change the air in my lungs, and I try to settle my thoughts on the task in hand.

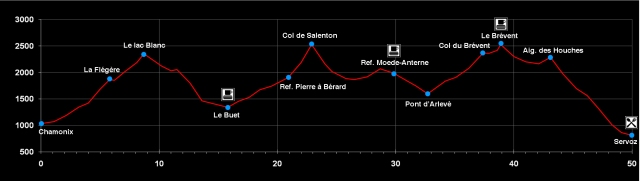

We run through the town for a kilometre on roads, probably the most I’ve ever run on tarmac since leaving school, and I am instantly pleased that I chose my Bushidos, which have a tiny bit of armour in them, over my much lighter, paper-thin soled Anakondas. My shins already screaming abuse at me, I am thankful when we turn north into the forest for the first big climb of the day, 1300m of ascent over 9km, up to Lac Blanc. We cross a stream, slowing to a crawl as one line files over a narrow bridge and another hops over stepping stones. Five hundred metres later, we approach another small stream, and people have stopped entirely to wait for their turn to use the bridge. Sod this, I mutter, maintaining speed and plunging one foot into the centre of the stream, overtaking five people in a single bound. I’ve had wet feet before, and I’ll have them again several times today.

We weave our way through the woods up to La Flegere, and as we climb higher towards Lac Blanc and above the treeline the scale of what we are doing reveals itself – the path all the way down to Chamonix is lit with hundreds of head torches, another hundred snake up out of view towards the lake, and, astonishingly, there are already a couple of spots of light flying towards the Tête au Vents in the distance to the north east, kilometres away and an hour into my future. Some of these people will go on to win, some others will drop out. A perfect starscape stretches over our heads, and the very faintest of yellow-green pre-dawn glow silhouettes the Aiguille du Chardonnet and the Aiguille du Tour, across the valley and a world away. My spirits soar as I draw energy from my surroundings, drinking it straight out of the sky (or maybe it was just from the first energy gel of the day, or my homemade Sports Honey). I keep wanting to nudge my neighbours’ ribs with an elbow, point at everything, and beam “Have you seen this?! Isn’t it incredible!!”, but the people around me seem to have their attentions focused elsewhere. I funnel my enthusiasm into my legs instead, and I’m shocked to find myself overtaking people… lots of people. I quickly settle into a system: I’ll catch up with the person in front of me and make a judgement of their health, depending on the size of the sweat patch covering their arse or how laboured their breathing is. If they are struggling, I’ll pip past them straight away, but if they are cruising along I’ll follow them for a few minutes to build my strength up, and then power on past them whenever the path allows.

I play this game until we reach our first high point of the day at Lac Blanc, an hour and forty after leaving town, but as we veer to the right and onto the descent path to the Col des Montets, everyone disappears, and I find myself in front of the dense throng that makes up the middle pack, with just the occasional headtorch out in front of me, winding their way down through the nature reserve on an incredibly technical trail. But it’s a trail I know well, having played on it for years and training on it heavily over the summer, and, hopping boulders and leaping over pitfalls, I zip past another twenty people on the way down to the col.

Daylight is nearly upon us, and I stash my torch on the run down to Buet, where Dan is waiting with apple juice and roast beef sandwiches. He tells me that I was ranked 109th back up at Lac Blanc, and, taken aback, I’m struck with a powerful urge to go and overtake more people, so I say my goodbyes. We press onwards into the Vallon de Bérard, with the Aiguille de Loriaz and Mont Oreb stealing the first rays of the rising sun, glowing a fiery orange as we traipse through a dew-drenched forest still under the shadow of dawn. With just a few steeper sections on an otherwise easy-angled ascent through the trees, a last taste of speed can be had on the way to the Refuge de la Pierre a Bérard. From there, though, up to the Col de Salenton, the climb gets progressively harder, at first on loose and crumbling earthy paths studded with landmine stones, just waiting to scurry out from under you at the first thoughtless foot placement, and then on dead-glacier domes and clean slabs, with the occasional lazily-balanced see-saw rock, eager to throw you over if you judge it wrong. The colours underfoot are incredible, a child’s drawing of a mountainscape: mauve and silver-lilac rocks covered with a hundred hues of green lichen, but this is small consolation during the climb. Hardly anyone puts the effort in to overtake here… if they do, they tire themselves out and drop back again minutes later. I fall in behind Giuseppe 190, who’s buttocks will often occupy my view for the remainder of the race, and we all grunt and swear our way up to the col, cursing the shifting rocks enthusiastically in a dozen languages.

At the col, with my knees starting to get the lactic squeezes (although, I have to say, a blueberry-based energy gel that I found with some kind of anti-oxidant magic worked wonders, and the cramps weren’t nearly so bad as the last time I was running over this way), I stop to breathe for sixty seconds, scanning the path ahead of us down the Vallon du Diosaz for any other runners – there are twos and threes and the occasional single dotted along the next 4km, until the path climbs up and right, out of sight behind the Tête de Moëde.

“Ça va?” a voice beside me says.

“Oui, merci, mais c’était difficile ça!” I pant, jabbing a thumb behind us.

“Cela été bien monté, toi.” Jean-Marc 624 intones, solemnly. “Bon descent,” he nods, setting off down the loose scree at the top of the western side of the Col de Salenton, his legs nothing but tightly-coiled bundles of wire. I’m exhausted, but after the faintest of praise from this stranger, I feel as though slacking off the pace would be failing him. I slide down the tumbling stones and gravel after him, grateful when the path turns into deeply-runneled banks of turf and then wide grassy plains. The wild, jagged north faces of the Floria and the Pouce tower over us to the south, recently snow-capped and in cool shade despite the high mid-morning sun; a cruel contrast to the rapidly-rising heat of the day.

I make it two kilometres on relatively friendly terrain before the cramps in my knees start screaming, and I have to slow down to a walk, gulping air into my lungs with my hands on my hips. “Run!” a voice shouts from behind me. I turn to see a ruddy-faced, barrel-chested man in a green T-shirt charging towards me. “You are in front of me, there is no reason to fall behind!”

With a sigh, a shrug, and a half-hearted “On y va!”, I heave myself into gear and fall in alongside him and his friend. “I was only enjoying the view for a moment…” I plead.

“No! To do that you must be happy!” he bellows, grinning widely, obviously implying that if you are happy, you aren’t trying hard enough. I speed up, and as the blood courses through my knees, the cramps clear and the resulting chemicals in this strange bodily function make their way to my heart and diaphragm, where they are hungrily devoured by hard-working muscles. I’m a little hazy on the specific chemistry, but this is the process behind breaking through the wall and getting your second wind. I am soon back sharing leads with Giuseppe (“Please, overtake if you’d like…” he says. “Impossible! I’d need a beer for that.”) and Jean-Marc, and charging towards our second revito at the Refuge du Moëde Anterne, where I enjoy a warm Coke and some orange wedges before tearing down to the Pont d’Arlevé, stumbling only once and plunging my left leg up to the thigh into a deep pool of sheep’s piss. Strangely, it lifts my mood, but probably doesn’t help my odour, which I am starting to notice as the now oppressive sun glares down on us.

From the bridge over the Diosaz torrent up to the summit of Le Brevent, we face our third big climb of the day, and our collective enthusiasm has started to wane. Half-a-dozen of us form a rag-tag group, taking turns to lead the way uphill, drawing no small degree of motivation from those behind. When not on lead, you can focus purely on your breathing and get your strength back, blindly following the footsteps of the person in front. The path steepens significantly a couple of kilometres before the summit of Brevent, and I suck down the last of my caffeine shots and yet another energy gel to prepare for it. “Oh, for fuck’s sake!” my stomach screams, “Not more of this shit! Give me a dry bowl of All-Bran, or some grated carrot, or anything with a bit of texture to it! I can’t work with this crap anymore!” and it tries to retch my gifts back up to me as I stride onwards, barely maintaining my composure. I promise it every vegetable under the sun if we can just tick off these last 15km, and at the third and final revito station at the top of Brevent I try to dilute the roiling, sticky hell in my guts with a pint of plain water. It does the trick, and after a few hundred metres of descent on a rabble of brutish shifting blocks, the path levels out for an undulating-but-easy grassy traverse under the gaze of the Tacul, Mont Maudit, Mont Blanc and the Dôme du Goûter. When I can find the occasional split second to tear my gaze from the path underfoot, I forget myself in the view. I’ve seen it a thousand times, and it never loses its impact.

Aiguille du Midi, Mont Blanc du Tacul, my floppy hair, Mont Maudit, Mont Blanc, Dôme du Goûter, Aiguille du Goûter

Another ascent appears in front of me, barely 150m of vertical to the top of the Aiguillette des Houches, a mere trifle, and the path is wide and welcoming. But after the previous eight hours, and with a couple of teasing false summits, the climb is a bitter battle to fight, and I nearly collapse in despair when I lay eyes upon the final descent ahead of me, the only section of the entire route that I’ve never seen before, and a truly sadistic touch from the route setters. We are now in for 1400m of an almost impossibly-steep descent, the first 400m of which is draped carelessly over one side of a knife-edged ridgeline, flying gravel and clouds of hot dust filling the narrow trenches carved into fields of alpenrose. As we plummet into the forest, the path becomes a seething mass of angry, scheming tree roots, and I give up, slowing down to a walk, head thrown back and wheezing through gritted teeth at the snarling pain in my right hip. As I hobble along, four people catch up with me one-by-one, and I gasp my best wishes to each as they overtake. The last one to pass misses his footing, rolls an ankle and shrieks in agony, standing perfectly still for a few seconds as I crawl onwards. Hopping forward, he tries his weight on it, screaming at each attempt – at first defeated, but growing defiant, until he is limping onwards at pace. But with barely five kilometres to go, I can’t break into a run for more than thirty seconds, and it seems I’ll be walking down to Servoz. Jean-Marc 624 trots up behind me. “Ça va?”

We chat in a mixture of English and French for a few minutes about injuries, hangovers, and ultra marathons as we stroll calmly along a rocky 4×4 track. “Okay to run from here?” he asks, our conversation having exhausted the obvious avenues. “It’s easier now.” After a few deep breaths I wish him a bon descent and break into a run, my legs once again loose enough to let gravity do some work.

Chalets start to appear in the trees, then the path drops you onto a thick ribbon of tarmac. “Nearly there!” the first marshal of many cheers, and I break into a sprint. The route goes back onto a damp path through the trees, and two hundred metres later the finish line still isn’t there so I slow down. “Nearly there!” another volunteer cries, and my feet are a blur again. After another 2km of this, they are finally correct, and the world starts filling with people and sound as the final corner is turned and the finish line looms towards you, and then suddenly, nine hours and nearly thirteen minutes after leaving Chamonix, there is no more run to run.

I honestly wasn’t expecting to complete the course as quickly as I did, and I would have been content simply to finish at all. But I am thrilled to bits to have finished in under ten hours, and I can only attribute that to the kind words and encouragements of the other runners… if I had been on just another one of my training jogs, I’d have spent more time walking and enjoying the view, giving in to the nagging demands of tired flesh and bone. I think I see, now, the appeal of this kind of competition: you aren’t really racing each other, you are racing the course, and you are all in it together.

Dan drives us back up the hill to Argentiere, and then we all talk nonsense as we rub champagne into our aching legs. As I flop into bed with a belly filled with roast pork and vegetables, the now-familiar question once again creeps to the front of my thoughts: what next?

(A thousand thank yous to Dan for the support and the pictures, to Georgie and Mary for the inspiration and occasional gibberish, and to every other runner who made this hellish ordeal such a fun day out. And, if you’d like, you can read about the at-times tedious preparations for the race in Episode 1. Cheers.)

Good job! I laughed out loud a few times whilst reading this. Made me wish I’d been there running all those trails. I’m almost sad summer is over but luckily winter and those long steep couloirs are round the corner…

Cheers dude, I’m so glad you enjoyed the read. Looking forward to reading about your December exploits…

Hat, Pete. Hat. Stunning achievement.

And great write up. You inspired me to run up some hills today.

Enjoyed the account. Reminded me of the time I ran in the Sierre/Zinal event some years ago but yours sounds harder. Best fun you can have in a group?

Pingback: Trail Running: Dorset Ultra CTS 2014 | Pete Houghton

Pingback: Trail Running: Crochues-Berard, and other short stories | Pete Houghton